巴菲特致伯克希尔股东的信

巴菲特致伯克希尔股东的信

《巴菲特致伯克希尔股东的信》由会员分享,可在线阅读,更多相关《巴菲特致伯克希尔股东的信(27页珍藏版)》请在装配图网上搜索。

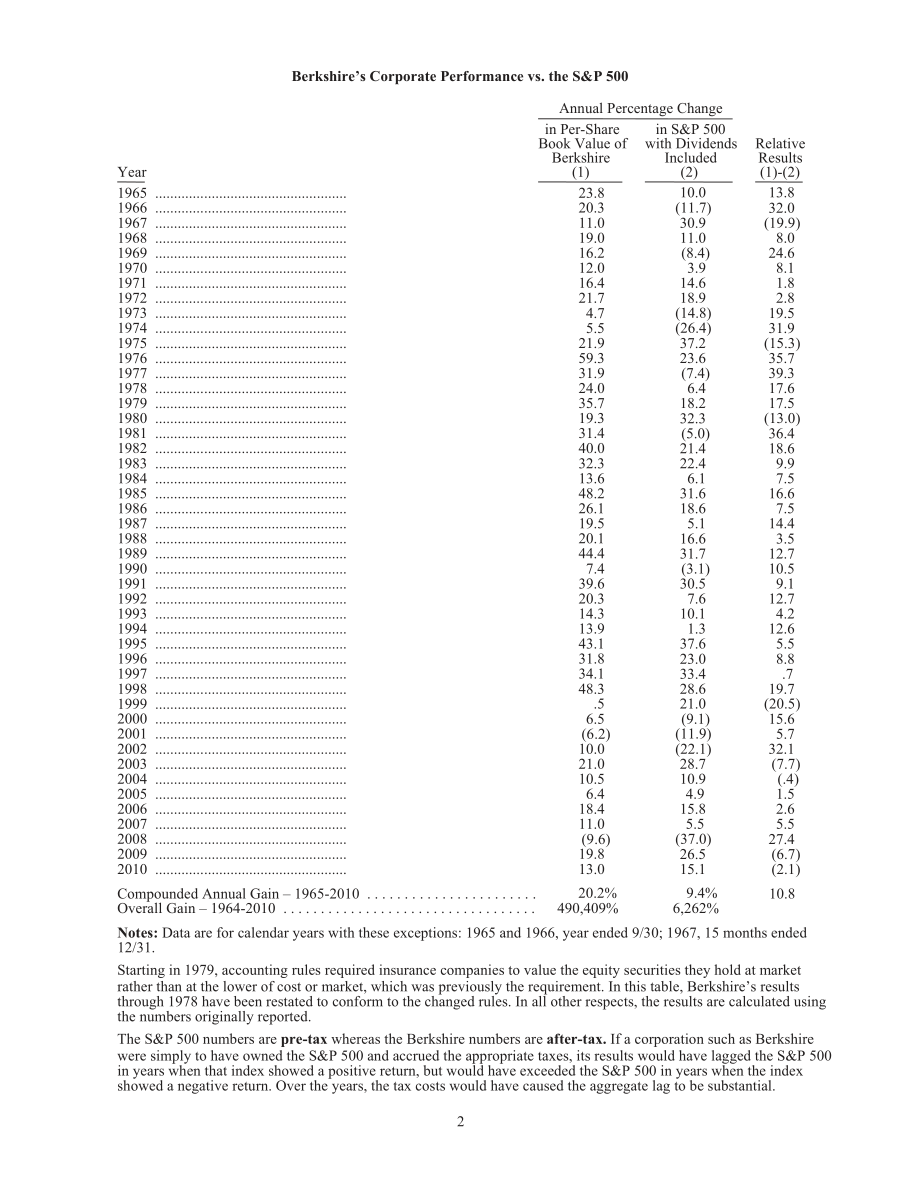

1、Berkshires Corporate Performance vs. the S&P 500Annual Percentage Changein Per-Sharein S&P 500Book Value ofBerkshirewith DividendsIncludedRelativeResultsYear(1)(2)(1)-(2)1965196619671968196919701971197219731974197519761977197819791980198119821983198419851986198719881989199019911992199319941995199619

2、971998199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010.23.820.311.019.016.212.016.421.74.75.521.959.331.924.035.719.331.440.032.313.648.226.119.520.144.47.439.620.314.313.943.131.834.148.3.56.5(6.2)10.021.010.56.418.411.0(9.6)19.813.010.0(11.7)30.911.0(8.4)3.914.618.9(14.8)(26.4)37.223.6(7.4)6.418.2

3、32.3(5.0)21.422.46.131.618.65.116.631.7(3.1)30.57.610.11.337.623.033.428.621.0(9.1)(11.9)(22.1)28.710.94.915.85.5(37.0)26.515.113.832.0(19.9)8.024.68.11.82.819.531.9(15.3)35.739.317.617.5(13.0)36.418.69.97.516.67.514.43.512.710.59.112.74.212.65.58.8.719.7(20.5)15.65.732.1(7.7)(.4)1.52.65.527.4(6.7)(

4、2.1)Compounded Annual Gain 1965-2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Overall Gain 1964-2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20.2%490,409%9.4%6,262%10.8Notes: Data are for calendar years with these exceptions: 1965 and 1966, year ended 9/30; 1967, 15 mo

5、nths ended12/31.Starting in 1979, accounting rules required insurance companies to value the equity securities they hold at marketrather than at the lower of cost or market, which was previously the requirement. In this table, Berkshires resultsthrough 1978 have been restated to conform to the chang

6、ed rules. In all other respects, the results are calculated usingthe numbers originally reported.The S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax. If a corporation such as Berkshirewere simply to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its results would h

7、ave lagged the S&P 500in years when that index showed a positive return, but would have exceeded the S&P 500 in years when the indexshowed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the aggregate lag to be substantial.2BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.To the Shareholders of Berkshire H

8、athaway Inc.:The per-share book value of both our Class A and Class B stock increased by 13% in 2010. Over thelast 46 years (that is, since present management took over), book value has grown from $19 to $95,453, a rate of20.2% compounded annually.*The highlight of 2010 was our acquisition of Burlin

9、gton Northern Santa Fe, a purchase thats workingout even better than I expected. It now appears that owning this railroad will increase Berkshires “normal”earning power by nearly 40% pre-tax and by well over 30% after-tax. Making this purchase increased our sharecount by 6% and used $22 billion of c

10、ash. Since weve quickly replenished the cash, the economics of thistransaction have turned out very well.A “normal year,” of course, is not something that either Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshireand my partner, or I can define with anything like precision. But for the purpose of estimating

11、our current earningpower, we are envisioning a year free of a mega-catastrophe in insurance and possessing a general businessclimate somewhat better than that of 2010 but weaker than that of 2005 or 2006. Using these assumptions, andseveral others that I will explain in the “Investment” section, I c

12、an estimate that the normal earning power of theassets we currently own is about $17 billion pre-tax and $12 billion after-tax, excluding any capital gains orlosses. Every day Charlie and I think about how we can build on this base.Both of us are enthusiastic about BNSFs future because railroads hav

13、e major cost and environmentaladvantages over trucking, their main competitor. Last year BNSF moved each ton of freight it carried a record500 miles on a single gallon of diesel fuel. Thats three times more fuel-efficient than trucking is, which meansour railroad owns an important advantage in opera

14、ting costs. Concurrently, our country gains because of reducedgreenhouse emissions and a much smaller need for imported oil. When traffic travels by rail, society benefits.Over time, the movement of goods in the United States will increase, and BNSF should get its fullshare of the gain. The railroad

15、 will need to invest massively to bring about this growth, but no one is bettersituated than Berkshire to supply the funds required. However slow the economy, or chaotic the markets, ourchecks will clear.Last year in the face of widespread pessimism about our economy we demonstrated our enthusiasmfo

16、r capital investment at Berkshire by spending $6 billion on property and equipment. Of this amount,$5.4 billion or 90% of the total was spent in the United States. Certainly our businesses will expand abroad inthe future, but an overwhelming part of their future investments will be at home. In 2011,

17、 we will set a newrecord for capital spending $8 billion and spend all of the $2 billion increase in the United States.Money will always flow toward opportunity, and there is an abundance of that in America.Commentators today often talk of “great uncertainty.” But think back, for example, to Decembe

18、r 6,1941, October 18, 1987 and September 10, 2001. No matter how serene today may be, tomorrow is alwaysuncertain.* All per-share figures used in this report apply to Berkshires A shares. Figures for the B shares are1/1500th of those shown for A.3Dont let that reality spook you. Throughout my lifeti

19、me, politicians and pundits have constantlymoaned about terrifying problems facing America. Yet our citizens now live an astonishing six times better thanwhen I was born. The prophets of doom have overlooked the all-important factor that is certain: Human potentialis far from exhausted, and the Amer

20、ican system for unleashing that potential a system that has worked wondersfor over two centuries despite frequent interruptions for recessions and even a Civil War remains alive andeffective.We are not natively smarter than we were when our country was founded nor do we work harder. Butlook around y

21、ou and see a world beyond the dreams of any colonial citizen. Now, as in 1776, 1861, 1932 and1941, Americas best days lie ahead.PerformanceCharlie and I believe that those entrusted with handling the funds of others should establishperformance goals at the onset of their stewardship. Lacking such st

22、andards, managements are tempted to shootthe arrow of performance and then paint the bulls-eye around wherever it lands.In Berkshires case, we long ago told you that our job is to increase per-share intrinsic value at a rategreater than the increase (including dividends) of the S&P 500. In some year

23、s we succeed; in others we fail. But,if we are unable over time to reach that goal, we have done nothing for our investors, who by themselves couldhave realized an equal or better result by owning an index fund.The challenge, of course, is the calculation of intrinsic value. Present that task to Cha

24、rlie and meseparately, and you will get two different answers. Precision just isnt possible.To eliminate subjectivity, we therefore use an understated proxy for intrinsic-value book value when measuring our performance. To be sure, some of our businesses are worth far more than their carryingvalue o

25、n our books. (Later in this report, well present a case study.) But since that premium seldom swingswildly from year to year, book value can serve as a reasonable device for tracking how we are doing.The table on page 2 shows our 46-year record against the S&P, a performance quite good in the earlie

26、ryears and now only satisfactory. The bountiful years, we want to emphasize, will never return. The huge sums ofcapital we currently manage eliminate any chance of exceptional performance. We will strive, however, forbetter-than-average results and feel it fair for you to hold us to that standard.Ye

27、arly figures, it should be noted, are neither to be ignored nor viewed as all-important. The pace ofthe earths movement around the sun is not synchronized with the time required for either investment ideas oroperating decisions to bear fruit. At GEICO, for example, we enthusiastically spent $900 mil

28、lion last year onadvertising to obtain policyholders who deliver us no immediate profits. If we could spend twice that amountproductively, we would happily do so though short-term results would be further penalized. Many largeinvestments at our railroad and utility operations are also made with an e

29、ye to payoffs well down the road.To provide you a longer-term perspective on performance, we present on the facing page the yearlyfigures from page 2 recast into a series of five-year periods. Overall, there are 42 of these periods, and they tellan interesting story. On a comparative basis, our best

30、 years ended in the early 1980s. The markets golden period,however, came in the 17 following years, with Berkshire achieving stellar absolute returns even as our relativeadvantage narrowed.After 1999, the market stalled (or have you already noticed that?). Consequently, the satisfactoryperformance r

31、elative to the S&P that Berkshire has achieved since then has delivered only moderate absoluteresults.Looking forward, we hope to average several points better than the S&P though that result is, ofcourse, far from a sure thing. If we succeed in that aim, we will almost certainly produce better rela

32、tive results inbad years for the stock market and suffer poorer results in strong markets.4Berkshires Corporate Performance vs. the S&P 500 by Five-Year PeriodsAnnual Percentage Changein Per-Sharein S&P 500Book Value ofBerkshirewith DividendsIncludedRelativeResultsFive-Year Period(1)(2)(1)-(2)1965-1

33、9691966-19701967-19711968-19721969-19731970-19741971-19751972-19761973-19771974-19781975-19791976-19801977-19811978-19821979-19831980-19841981-19851982-19861983-19871984-19881985-19891986-19901987-19911988-19921989-19931990-19941991-19951992-19961993-19971994-19981995-19991996-20001997-20011998-2002

34、1999-20032000-20042001-20052002-20062003-20072004-20082005-20092006-2010.17.214.713.916.817.715.013.920.823.424.430.133.429.029.931.627.032.631.527.425.031.122.925.425.624.418.625.624.226.933.730.422.914.810.46.08.08.013.113.36.98.610.05.03.99.27.52.0(2.4)3.24.9(0.2)4.314.713.98.114.117.314.814.619.

35、816.415.220.313.115.315.814.58.716.515.220.224.028.518.310.7(0.6)(0.6)(2.3)0.66.212.8(2.2)0.42.312.210.84.79.315.717.410.715.923.620.115.419.520.915.814.312.218.011.711.09.810.89.810.19.89.99.99.19.06.79.71.94.64.111.06.610.37.46.90.59.18.27.7Notes: The first two periods cover the five years beginni

36、ng September 30 of the previous year. The third period covers63 months beginning September 30, 1966 to December 31, 1971. All other periods involve calendar years.The other notes on page 2 also apply to this table.5Intrinsic Value Today and TomorrowThough Berkshires intrinsic value cannot be precise

37、ly calculated, two of its three key pillars can bemeasured. Charlie and I rely heavily on these measurements when we make our own estimates of Berkshiresvalue.The first component of value is our investments: stocks, bonds and cash equivalents. At yearend thesetotaled $158 billion at market value.Ins

38、urance float money we temporarily hold in our insurance operations that does not belong to us funds $66 billion of our investments. This float is “free” as long as insurance underwriting breaks even, meaningthat the premiums we receive equal the losses and expenses we incur. Of course, underwriting

39、results are volatile,swinging erratically between profits and losses. Over our entire history, though, weve been significantlyprofitable, and I also expect us to average breakeven results or better in the future. If we do that, all of ourinvestments those funded both by float and by retained earning

40、s can be viewed as an element of value forBerkshire shareholders.Berkshires second component of value is earnings that come from sources other than investments andinsurance underwriting. These earnings are delivered by our 68 non-insurance companies, itemized on page 106.In Berkshires early years, w

41、e focused on the investment side. During the past two decades, however, weveincreasingly emphasized the development of earnings from non-insurance businesses, a practice that willcontinue.The following tables illustrate this shift. In the first table, we present per-share investments at decadeinterv

42、als beginning in 1970, three years after we entered the insurance business. We exclude those investmentsapplicable to minority interests.Per-ShareCompounded Annual IncreaseYearendInvestmentsPeriodin Per-Share Investments1970 .$661980199020002010.7547,79850,22994,7301970-19801980-19901990-20002000-20

43、1027.5%26.3%20.5%6.6%Though our compounded annual increase in per-share investments was a healthy 19.9% over the40-year period, our rate of increase has slowed sharply as we have focused on using funds to buy operatingbusinesses.The payoff from this shift is shown in the following table, which illus

44、trates how earnings of ournon-insurance businesses have increased, again on a per-share basis and after applicable minority interests.Per-ShareCompounded Annual Increase inYearPre-Tax EarningsPeriodPer-Share Pre-Tax Earnings1970 .$2.871980199020002010.19.01102.58918.665,926.041970-19801980-19901990-

45、20002000-201020.8%18.4%24.5%20.5%6For the forty years, our compounded annual gain in pre-tax, non-insurance earnings per share is 21.0%.During the same period, Berkshires stock price increased at a rate of 22.1% annually. Over time, you can expectour stock price to move in rough tandem with Berkshir

46、es investments and earnings. Market price and intrinsicvalue often follow very different paths sometimes for extended periods but eventually they meet.There is a third, more subjective, element to an intrinsic value calculation that can be either positive ornegative: the efficacy with which retained

47、 earnings will be deployed in the future. We, as well as many otherbusinesses, are likely to retain earnings over the next decade that will equal, or even exceed, the capital we presentlyemploy. Some companies will turn these retained dollars into fifty-cent pieces, others into two-dollar bills.This

48、 “what-will-they-do-with-the-money” factor must always be evaluated along with the“what-do-we-have-now” calculation in order for us, or anybody, to arrive at a sensible estimate of a companysintrinsic value. Thats because an outside investor stands by helplessly as management reinvests his share of

49、thecompanys earnings. If a CEO can be expected to do this job well, the reinvestment prospects add to thecompanys current value; if the CEOs talents or motives are suspect, todays value must be discounted. Thedifference in outcome can be huge. A dollar of then-value in the hands of Sears Roebucks or

50、 MontgomeryWards CEOs in the late 1960s had a far different destiny than did a dollar entrusted to Sam Walton.*Charlie and I hope that the per-share earnings of our non-insurance businesses continue to increase at adecent rate. But the job gets tougher as the numbers get larger. We will need both go

51、od performance from ourcurrent businesses and more major acquisitions. Were prepared. Our elephant gun has been reloaded, and mytrigger finger is itchy.Partially offsetting our anchor of size are several important advantages we have. First, we possess acadre of truly skilled managers who have an unu

52、sual commitment to their own operations and to Berkshire.Many of our CEOs are independently wealthy and work only because they love what they do. They arevolunteers, not mercenaries. Because no one can offer them a job they would enjoy more, they cant be luredaway.At Berkshire, managers can focus on

53、 running their businesses: They are not subjected to meetings atheadquarters nor financing worries nor Wall Street harassment. They simply get a letter from me every two years(its reproduced on pages 104-105) and call me when they wish. And their wishes do differ: There are managersto whom I have no

54、t talked in the last year, while there is one with whom I talk almost daily. Our trust is in peoplerather than process. A “hire well, manage little” code suits both them and me.Berkshires CEOs come in many forms. Some have MBAs; others never finished college. Some usebudgets and are by-the-book type

55、s; others operate by the seat of their pants. Our team resembles a baseball squadcomposed of all-stars having vastly different batting styles. Changes in our line-up are seldom required.Our second advantage relates to the allocation of the money our businesses earn. After meeting theneeds of those b

56、usinesses, we have very substantial sums left over. Most companies limit themselves toreinvesting funds within the industry in which they have been operating. That often restricts them, however, to a“universe” for capital allocation that is both tiny and quite inferior to what is available in the wi

57、der world.Competition for the few opportunities that are available tends to become fierce. The seller has the upper hand, asa girl might if she were the only female at a party attended by many boys. That lopsided situation would be greatfor the girl, but terrible for the boys.At Berkshire we face no

58、 institutional restraints when we deploy capital. Charlie and I are limited onlyby our ability to understand the likely future of a possible acquisition. If we clear that hurdle and frequently wecant we are then able to compare any one opportunity against a host of others.7When I took control of Ber

59、kshire in 1965, I didnt exploit this advantage. Berkshire was then only intextiles, where it had in the previous decade lost significant money. The dumbest thing I could have done was topursue “opportunities” to improve and expand the existing textile operation so for years thats exactly what Idid.

60、And then, in a final burst of brilliance, I went out and bought another textile company. Aaaaaaargh!Eventually I came to my senses, heading first into insurance and then into other industries.There is even a supplement to this world-is-our-oyster advantage: In addition to evaluating theattractions o

61、f one business against a host of others, we also measure businesses against opportunities available inmarketable securities, a comparison most managements dont make. Often, businesses are priced ridiculouslyhigh against what can likely be earned from investments in stocks or bonds. At such moments,

62、we buy securitiesand bide our time.Our flexibility in respect to capital allocation has accounted for much of our progress to date. We havebeen able to take money we earn from, say, Sees Candies or Business Wire (two of our best-run businesses, butalso two offering limited reinvestment opportunities

63、) and use it as part of the stake we needed to buy BNSF.Our final advantage is the hard-to-duplicate culture that permeates Berkshire. And in businesses,culture counts.To start with, the directors who represent you think and act like owners. They receive tokencompensation: no options, no restricted

64、stock and, for that matter, virtually no cash. We do not provide themdirectors and officers liability insurance, a given at almost every other large public company. If they mess upwith your money, they will lose their money as well. Leaving my holdings aside, directors and their families ownBerkshir

65、e shares worth more than $3 billion. Our directors, therefore, monitor Berkshires actions and resultswith keen interest and an owners eye. You and I are lucky to have them as stewards.This same owner-orientation prevails among our managers. In many cases, these are people who havesought out Berkshir

66、e as an acquirer for a business that they and their families have long owned. They came to uswith an owners mindset, and we provide an environment that encourages them to retain it. Having managerswho love their businesses is no small advantage.Cultures self-propagate. Winston Churchill once said, “You shape your houses and then they shapeyou.” That wisdom applies to businesses as well. Bureaucratic procedures beget more bureaucracy, and imperialcorporate palaces induce imperious behavior. (As o

- 温馨提示:

1: 本站所有资源如无特殊说明,都需要本地电脑安装OFFICE2007和PDF阅读器。图纸软件为CAD,CAXA,PROE,UG,SolidWorks等.压缩文件请下载最新的WinRAR软件解压。

2: 本站的文档不包含任何第三方提供的附件图纸等,如果需要附件,请联系上传者。文件的所有权益归上传用户所有。

3.本站RAR压缩包中若带图纸,网页内容里面会有图纸预览,若没有图纸预览就没有图纸。

4. 未经权益所有人同意不得将文件中的内容挪作商业或盈利用途。

5. 装配图网仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对用户上传分享的文档内容本身不做任何修改或编辑,并不能对任何下载内容负责。

6. 下载文件中如有侵权或不适当内容,请与我们联系,我们立即纠正。

7. 本站不保证下载资源的准确性、安全性和完整性, 同时也不承担用户因使用这些下载资源对自己和他人造成任何形式的伤害或损失。